For a man who has only recently started his job, international development minister Nick Hurd seems sure of his priorities.

“Energy Africa makes perfect sense to me,” he says. “In the next few weeks and months we’re going to be shaping what DfID [the Department for International Development] does in the next five, arguably 10 years. But improving access to energy in Africa is my particular focus at the moment.”

After spending four years as minister for civil society under the coalition government, Hurd has been parachuted into the job at DfID to replace Grant Shapps, who resigned in the midst of allegations that bullying in the Tory party had led to the death of one of its activists.

Although his new portfolio covers a range of issues including water, climate change, sanitation, education and health, his immediate priority is to “keep up the momentum” of the Energy Africa campaign launched by Shapps in October.

Hurd has his sights set on the seventh sustainable development goal: universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services by 2030. But sub-Saharan Africa is currently 50 years behind, the only region in the world where the number of people denied access to modern forms of energy is set to rise and, based on current trends, predicted to hit the goal by 2080.

Inspired by Barack Obama’s flagship Power Africa programme, Hurd hopes that Energy Africa can make a key difference. Last month the US and UK projects came together to create a new partnership to address specific issues such as the need for shared power across borders, resources for geothermal power, and to boost the number of women participating in Africa’s solar industry.

But unlike Power Africa, which has been catalysing a wide range of renewable energy projects that will connect to the national grid – from a vast solar farm in Rwanda to the first wind power project in Senegal – Energy Africa has a very specific objective: to accelerate off-grid solar power for households using private investment.

Grid investment will only reach 40% of the population and leave more than 500 million people still without electricity access in 2030, according to the Overseas Development Institute. Critics say that the impact of DfID’s campaign will be only “incremental” because the continent needs large-scale infrastructure and while NGOs push decentralisation, Africans want a grid connection.

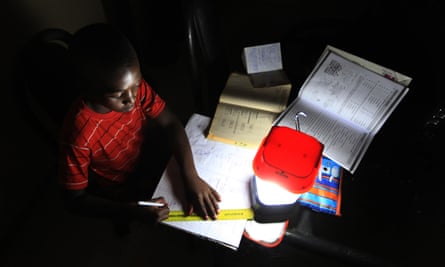

But it is well known that these incremental changes can create significant new possibilities in the lives of individuals and communities, from lanterns that enable pupils to study at night, to mobile phone chargers, to lights for huts that keep animals safe from predators.

Hurd is adamant about the need and value of off-grid investment. “The question is: what can we do for the 60% now?” he asks. “It strikes a chord with ministers wrestling with energy access in their countries. On-grid is massively important but most of the projections suggest that’s going to take a long time and won’t reach all the population. That’s why Energy Africa is focused on household solar energy. We think there is huge potential in off-grid particularly, because we see this market developing which we think we, with partners, can turbo charge.”

A host of factors have coalesced to create what Hurd describes as a “pivotal moment” for household solar in Africa. In the past six years, the price of panels has dropped by around 70%, making it as cheap as fossil fuels in some areas. The price and quality of battery technologies is also improving fast while the spread of mobile money systems on the continent is making solar an increasingly feasible prospect for the individual householder.

Six countries have signed up to DfID’s Energy Africa campaign. Ministers from Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Somalia were the first to complete an agreement, followed by Ghana, Malawi and Rwanda. Eight other countries have been identified as potential targets, including Zimbabwe, Ethiopia and Uganda.

The countries were chosen because they were “biting our hand off” says Hurd. “We are responding to demand.”

Working in fragile states is one of DfID’s explicit objectives, partly driven by national security interests. More than half its budget is committed to work in such regions, but implementing clean energy is a challenge in states grappling with terrorism and conflict, such as Nigeria and Somalia.

Problems vary from country to country, but the industry has been held back by a lack of legal and tax structures. The International Finance Corporation is currently working to establish a new set of product standards. DfID say it is its role to work out how to streamline the bureaucracy, and the specific challenges in each country are still being identified.

Providing electricity at the household level comes with additional challenges. For rural communities miles from a grid connection, energy poverty is entrenched by lack of access to financial systems. Pay-as-you-go schemes offered by mobile phones are changing this, but penetration fluctuates from country to country. DfID hopes that the campaign will be able to support non-bank financial providers to create mobile payment systems. In places where regulation makes it unfeasible, alternatives such as scratch cards will make up the difference.

The campaign is not a “traditional aid programme” says Hurd. Its aim is to galvanise private investment in countries where DfID has formed a partnership with the government. “It’s a different model,” he says. “It’s not about a huge chunk of public money; it’s not a DfID programme as such. It’s a private-sector solution to this challenge.”

But in a debate where creating clean energy is often pitted against economic development, it does not yet seem to be clear how foreign investment galvanised by the campaign will provide substantial jobs for Africans on the ground.

Although DfID has previously given seed funding to mobile money solar companies in the UK and Africa – such as Azuri Technologies and Persistent Energy Ghana – the majority of investors involved in the campaign will be foreign, with many British companies involved.

“We’re not nationalistic about this. We know it’s going to be private-sector led and we want to support entrepreneurs. At the moment most of the businesses are foreign, but over time my hope and expectation is that this will evolve. There is a hell of a lot going on in trying to increase energy access in Africa. My overriding instinct is to keep asking the question: how does this join up?”

Join our community of development professionals and humanitarians. Follow @GuardianGDP on Twitter. Join the conversation with the hashtag #EnergyAccess.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion