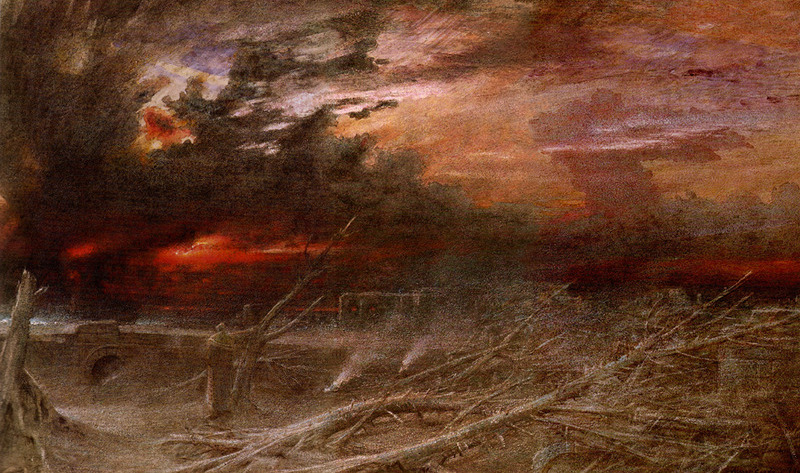

And If This Is(n’t) the End of the World? Why We Dread—and Desire—Apocalypse

Alex Foster on What Draws Us to Doomsday Fantasies, and Why We Should Resist the Urge to Indulge Them

When the end of the world arrived in 1349, flagellants took to the streets to hasten it along. Whipping themselves in shirtless processions, they preached that the Black Death, which was tearing apocalyptically through Europe at the time, was divine punishment for society’s failure. They would whip themselves as a way of accepting and augmenting that punishment, in support of God’s apparent readiness to draw the final curtain on humanity. Ultimately, the plague killed about one third of Europe, which is to say, it left two thirds alive and mourning, perhaps wondering why the apocalypse had stopped short.

We commonly think of the end of the world as something feared, but the truth is that in 1349, as in 2025, our apocalypticism betrays a certain longing. These days, the apocalypse seems to be on everyone’s minds. Four in ten U.S. adults believe humanity is “living in the end times.” Our climate crisis, our presidential campaigns, war, and AI are all routinely ascribed with existential stakes—not without reason.

Every generation believes it might be the last, but some generations have a stronger basis for that belief than others. Ours seems to be a generation particularly preoccupied by the possibility. Even, I argue, enamored with it: In all the fervor with which we anticipate our doom these days (the sensationalist headlines; the superhero flicks showing our cities neatly destroyed), it seems the prospect of an “end” holds some kind of perverse appeal.

In such times, it is less painful to dream of an ending than to consider the alternative: that hardship just keeps going on and on, maybe even getting worse.In our time, it’s not just religious fanatics. Across the political and cultural spectrum, while conceptions of the apocalypse differ, Americans who disagree on everything are agreeing that the world is so bad that it should end. They don’t fear the apocalypse will come; they fear it won’t.

*

It’s hard not to see the election of Trump as one expression of this death-wish. Evangelicals have endorsed Trump explicitly as an eschatological figure, one who heralds the end times. It’s said that Mike Huckabee, Trump’s Christian Zionist pick for ambassador to Israel, hopes his geopolitics will trigger the end of days. But more broadly, even voters who don’t subscribe to that kind of Christian fundamentalism seem fond of Trump as a figure of cataclysm. A tenth of his voters said they wanted America’s economic and political system “torn down entirely.”

Trump famously asked Black voters, “What the hell do you have to lose,” implying that whatever they might have in life (right up to life itself?) is so unappealing it’d be better to lose it than keep it as is, and “Nothing to Lose” was taken up by some as a personal slogan for their support of Trump. Trumpian political fantasies revolve around destruction (of federal agencies, of the Affordable Care Act) without any plan for what comes next—they fixate on “endings” while blocking out any consideration that something next must come.

On the Left, catastrophists in the “Abrupt Climate Change” movement predict human extinction this decade, and in the past year, philosophy books like Todd May’s Should We Go Extinct? have raised the level-headed argument that our demise could be a moral good for the planet. Divorced from political partisanship, “Antinatalists” argue that humans should induce our own extinction by refusing to have any more children—not for the planet’s sake, but for the kids’: to spare them the agony of human life. In her latest standup special, Broad City star Ilana Glazer describes first laying eyes on her newborn daughter: “They look at you like, ‘Why am I here?’ I don’t know…Also, like, welcome to hell. Sorry…You’re gonna be so mad.” Everyone seems to know what she means.

Are the youth in agony here? Suicide among Americans aged ten to twenty-four is up 62% since the start of the millennium. An astounding one in ten American high schoolers have attempted suicide. Corners of social media, in which teen suicides have been live-streamed and emulated, have organized into a sort of death cult. It’s not just our online youth, though: Fifteen- to twenty-four-year-olds still have the lowest suicide rate of any age bracket. Suicide is rising for all Americans. You get the clear impression that our society at large is one in which people are less and less inclined to carry on. They are pursuing—not avoiding—annihilation at the scale available to them.

And their complaint is with society at large. Although we’re often pushed to blame ourselves for our despair (by wellness companies, for example, that sell us personalized medications and meditation apps to treat our own individual imbalances), still, 2020s Americans seem to recognize that “it’s not just me, it’s the world.” Take our approach to therapy: we seek out “climate-aware” therapists to address our anxiety around global warming; more and more therapists are being trained to discuss issues of race and privilege; and whereas mid-century psychiatrists gave upset housewives sedatives and ECT, people today learn about social structures that can oppress women and degrade their mental health.

To my mind, the Americans who have most fully connected their misery to systemic forces are Gen-Z, the “Doomer generation.” Surf r/Doomer on any given week (or even r/GenZ, for that matter), and one of the most striking and persistent things you’ll find is that the suicide threats are posted as comments on news headlines. They are a response to the state of humanity.

We need to do the right thing not because the world is at stake, but because it almost surely isn’t—the world will persist, and we’re going to be stuck in it.Perhaps it’s in this connection—between the individual’s suffering and her view of society—that the rise in depression becomes a desire for apocalypse. Every day, you can find Americans posting on social media that society is not only insufferable for them, but so hostile to so many, that it can’t possibly go on much longer. That it shouldn’t go on much longer. It seems that what so many of us may really want (though most of us only want it a little bit, a morbid fantasy in our darker hours) is not an end to ourselves, but an end to the world.

In researching for this article, I routinely saw r/Doomer posts claiming that humankind must be on the verge of “unprecedented” cataclysm. When someone responds with the obligatory “Nothing Ever Happens” meme, it doesn’t reassure the community—it devastates them.

Why do we want cataclysm?

Maybe it is that the guilty seek punishment. We are a cripplingly guilty society. David Graeber in Bullshit Jobs and others have documented modern Americans’ tendency to believe (rightfully, perhaps) that our occupations have a negative impact on the world. Right- and left-wingers believe our American culture offends God or the planet or one another. Even many who work in nonprofits are quick to tell you that they know they’re “part of the problem.” Some of this self-debasement is performative, but it sinks in, and we, like three hundred million Raskolnikovs, anticipate our comeuppance in every encounter.

Or maybe we really fear that the end is nigh, that our parents doomed us and now it’s out of our hands. And seeing the world slipping, we act tough and say we don’t care about saving it. It’s like we’re quitting before we can be fired. I once taught a class of undergraduates who told me that whereas my generation (only six years older than them) got all up in arms about the world’s problems, they knew it was hopeless. “We’re just like, whatever,” one said. They wouldn’t let themselves care what happens to the world. (Notably, that conversation started from my students attempting to explain to me the humor in a certain Tiktok video, which showed a teen ecstatically dancing, then addressing the camera to say he was going to kill himself.)

Such self-jading is natural. A Black Death-era chronicler who announced “the end of the world” noted that “nobody wept no matter what his loss because almost everyone expected death.” We cope by thinking, “What the hell do I have to lose?” Naturally, one becomes numb to the good in life too. The chronicler again: “In these days was burying without sorrow and wedding without friendship.”

But what I think so many of us really fear is that the world isn’t ending. Apocalypse has always been an escapist fantasy in unendurable times. The Book of Revelation was composed under brutal conditions of Roman colonization. The concept of “Rapture,” that vision pursued by today’s right-wing evangelicals, wasn’t added to the theology until the American Civil War—another time when society seemed an unending, internecine hell. In such times, it is less painful to dream of an ending than to consider the alternative: that hardship just keeps going on and on, maybe even getting worse.

It makes sense to dream of an end if you believe we’ll never solve our problems. If you believe that new technologies are being developed to fortify racial and class oppression. Or if you, like me, have nightmares about the ecological forecasts described in books like David Wallace-Wells’s The Uninhabitable Earth. As I write this, we’re on track for another hottest year on record, and the president is dismantling the social services we’ve relied on. The future is not looking brighter than the past. In fact, it’s looking very scary. Perhaps it won’t come. A nation can dream.

But we shouldn’t. We ought to call out these pervasive fantasies of annihilation.

That doesn’t mean that the correct response to apocalypticism is the “Nothingburger” meme, the one captioned “Nothing Ever Happens.” In that all-too-common online exchange, the disconnect between the two sides is glaring: There is a failure to imagine the world of possibility (indeed, the entire world of likelihood) in the middle—that things do happen, and life gets either better or worse. Not Earth-shatteringly. Not existentially. The last election may not prove to have been a “last chance to save America.” But we had plenty to lose in that election. We may lose more still in the next one.

We need to do the right thing not because the world is at stake, but because it almost surely isn’t—the world will persist, and we’re going to be stuck in it, and quotidian shifts are going to matter. Maybe not to the universe, but to the individual. I only have one life. A few decades more at most. Whether I spend them amidst wildfire smoke or fresh air, in peace or in war, in a nation of loathing and locked doors or one of trust and equality…that means, almost, the world to me.

__________________________________

Circular Motion by Alex Foster is available from Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic.